![exile feature1-1 detdom tynda1]()

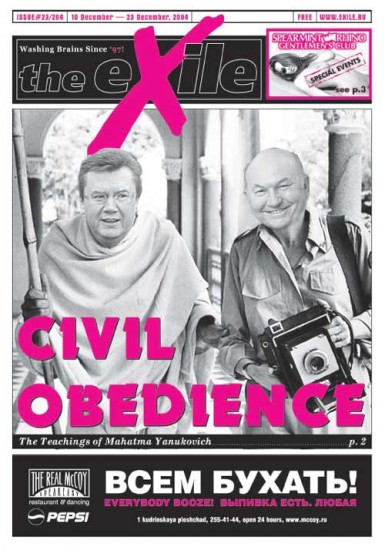

This article was first published in The eXile on January 22, 2003

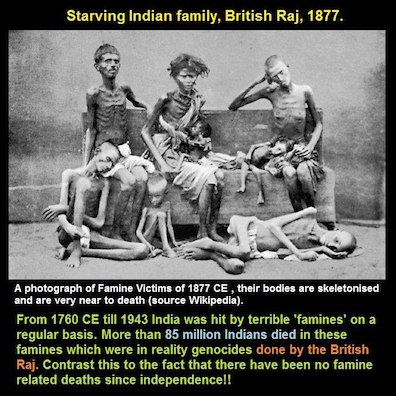

Dima’s eyes lit up when he first saw the Solnyshko orphanage’s toy collection two months ago. He had never seen anything like it. It took me a few moments of staring at the same collection last week for it to register that the pile of ratty animals with ears worn from having been sucked on by untold numbers of orphans could cause such joy.

But then, I’m not a three-year-old who used to survive by rooting around trash heaps looking for something to eat. Dima is.

He was brought to the Solnyshko with his older brother and sister from a small village after neighbors alerted the militsia that the kids were being neglected. Neglected in this case meant living in an abandoned wagon without running water and scavenging for food because his parents were too always too drunk to feed him. He had never seen a toy before and suffered from severe malnutrition.

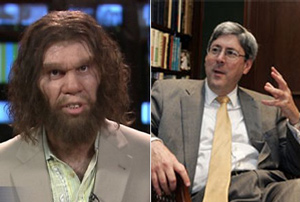

Horrible as it sounds, Dima’s story doesn’t raise eyebrows among his peers at the orphanage. According to Stanislav Tishenko, the Solnyshko’s lone psychologist, “For these children, that’s just life.”

Tishenko, a large, soft spoken man in his early 30s, knows the story of every child who has passed through the Solnyshko, and told me dozens of them. While he was reciting what some of these kids have lived through, I saw a Russian man cry for the first time in more than four years living here.

Masha, who spent a year at Solnyshko, was also three when her alcoholic mother ditched her in Tynda’s train station. After some time alone, a drunken couple noticed the terrified little girl and brought Masha back to their apartment. They soon lost interest in their acquisition, though, and continued their drinking binge. They finally passed out, at which point their 14-year-old son raped Masha repeatedly. By the time the parents woke up, blood was pouring down both Masha’s legs and she was in critical condition. So they sneaked her out to the street and left her to die. A chance passerby rushed Masha to the hospital. Surgeons were helicoptered in from Blagaveshensk to save her life. Masha is now nine years old, infertile and believes that Baba Yaga did all those horrible things to her.

At the age of seven, Yasya was put in Solnyshko because his mother killed his father when she found out he was cheating on her. Due to the extenuating circumstances, she got a relatively light sentence. She seemed genuinely regretful and, while in prison, wrote long, loving letters to Yasya. The staff at Solnyshko encouraged the boy to think of her release as his salvation. But once she got out, she disappeared without a trace. Several months later she finally picked him up. Three days after their reunion, she murdered a woman in front of Yasya. He was placed back in Solnyshko and, as the only witness to the crime, made to testify against her. During the trial, while locked in a cage full of prisoners awaiting conviction, his mother saw him and swore she would kill him, her only son.

Four preteen siblings came to Solnyshko after having spent nearly two months living with their mother and the corpse of their father, who had been axed by mom during a drunken rampage. He didn’t rot, because the apartment had no heating, and the kids were only found after the neighbors alerted the militsia that they hadn’t heard from them in a long time. The youngest girl didn’t talk for months afterwards.

![feature3-1 tynda2]()

Those are all real stories from the last few years at the Solnyshko. Tishenko has an equally tragic and revolting history for just about every one of the some 400 kids who have passed through the orphanage’s doors since it opened in 1995. They arrive at the Solnyshko malnourished and sick, having recently been seized by Social Services from abusive, drunken parents who often resist giving up their children. Most have varying degrees of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. Many of them have had to beg or steal to feed themselves. Some haven’t been to school in months, while others never have. They show up in t-shirts in the winter, because their parents pawned their clothing and everything else of any worth for alcohol. It’s up to Tishenko and the rest of the staff to try to impart enough strength and know-how to prevent them from following in their parents’ footsteps.

The Solnyshko is in Chilchi, about five hours northeast of Tynda. It is one of the unrealized towns along the BAM that withered along with the rest of the magistrate. Some 5000 people lived in wagons during the construction of the town, but then the funding dried up and the project halted. Only three five-story apartment buildings, a school, a kindergarten, an impressive station and one street (ulitsa Lenina) were ever built. The population has dwindled to 500. Less than a mile out of Chilchi, an eerie ghost town composed of wagons long since looted for their valuable parts is slowly fading into the taiga.

Just as most people were shipping out, a smaller second wave of Slavic settlers arrived to escape rising nationalism in Central Asia. They chose Chilchi because moving to such an undesirable place was one of the few ways to insure that they would get an apartment and citizenship in Russia. Among the new arrivals were several pedagogues.

However, with the steep drop in population, there was no reason to maintain a kindergarten. Over the same period, between 1992 and 1995, the orphanage system throughout Russia was in a profound crisis. The number of children without parental care nearly doubled to 113,000 new cases annually. It has since stabilized at around that staggering number.

In 1995, the kindergarten was hastily converted into the Solnyshko, an orphanage to serve the four northeastern-most regions of the Amurskaya oblast.

There are several advantages in having an orphanage in Chilchi, the most obvious being that there’s nowhere to run away to because it’s in the middle of the taiga. The tight-knit community – there are only two stores – also means that the kids can’t buy alcohol anywhere or get away with skipping school. And, since these kids make up nearly half the student body at the school, they are well integrated and teachers know that they often require special care. There’s also a tacit understanding that without the Solnyshko and the 40 jobs it brings to Chilchi, the town would have been shuttered up long ago.

The Solnyshko is actually a priyut, which means that it functions as a stopgap to inject kids into the ridiculously overcrowded and dilapidated Russian orphanage system. Priyuts are a relatively new measure, born in the 90s. But even after their advent, the system is so strained by the influx of abandoned children in recent years that kids often have to spend several months living in the children’s ward of a hospital before space in a priyut frees up. The system remains a complete mess, stranded somewhere between dated Soviet and more progressive methods. It has no cohesive ideology and barely enough funding to survive, let alone consider undertaking serious reform. What awaits a kid caught in the system depends on the management of the individual home.

In the Amurskaya oblast there are eight priyuts, each serving one or several regions. After living in a priyut for about six months to a year, depending on when a space becomes available, kids are then transferred into one of 20 detdoms, or long-term orphanages, throughout the oblast. Siblings are kept together.

According to Tishenko, priyuts tend to be more humane than other Russian orphanages, as they only started opening in the mid-90s and their directors tend to know at least a modicum of current child-rearing theories. Tishenko himself began working at the priyut in 1996 without any experience in child psychology. He is now in his third year in a correspondence program with a Moscow university for a degree in psychology (which he pays for himself). He is the Solnyshko’s only trained professional.

Male pedagogues are quite rare in Russia, but Tishenko has an intensely personal reason for picking his profession. He spent four years of his childhood living in a mammoth Soviet detdom. He now often comforts the kids at the Solnyshko by telling horror stories from back then. The kids immediately pick up on his empathy, and often trust him more than any other authority figure in their lives.

Priyuts also have the advantage of being much smaller, holding about 40 beds, compared with the 150 to 200 in most detdoms, which means that kids get more individual attention than they would in the larger institutions. 15- and 16-year-olds who enter a priyut generally can bypass detdoms entirely and enter an uchilsche, or boarding school that teaches a trade of dubious value, such as woodworking or taxidermy. Virtually all the kids are bad students; only a single girl who passed through the Solnyshko went on to graduate from a college, the lowest level of higher education in Russia.

Most kids just stay in a detdom until they turn 18. Of all the detdoms in the oblast, Tishenko only approves of the one in Konstantinov. However, even that one hardly seems ideal. In a letter from Sasha, one of his former pupils now in Konstantinov, she wrote, “They don’t worry about whether or not our parents write us or whether or not they have died in this detdom. Here everyone minds his own business. I know that you worried about every kid, while here nobody needs us. Whether kids cry or not is all the same to them.” It is decent, Tishenko said, because they feed and clothe the children well and the authorities are not abusive. A letter he read me from a 13-year-old boy in another detdom asked him to send socks and mittens, because the detdom doesn’t distribute them to the kids.

According to Olga Kravchenko, the shoulder-padded archetypal Soviet pedagogue who directs the Solnyshko, priyuts technically serve several constituencies; they offer temporary shelter for kids who are having problems at home, and also let parents place their children there during times of financial hardship, in the event of a disaster like a house fire, or if their work prevents them from being able to take care of their kids. Solnyshko even has two North Korean brothers whose parents manage an army of forced laborers logging the taiga. However, such short-term assistance is an afterthought. About 90 percent of the kids at Solnyshko are waiting to be assigned a slot in an orphanage because their alcoholic parents abandoned them. “Our main task is to help bring these kids back into society,” Kravchenko said. “Or sometimes introduce them to society for the first time.”

Most Russian orphans are not orphans at all; they are victims of this country’s raging problem with alcoholism. Their parents are still alive. They’re just dead drunk.

For those who have never seen it, it’s difficult to comprehend what Tishenko calls the “systematic approach to drinking” of alcoholics out here. It’s when people black with grime and soot don’t bathe for weeks because they’re too drunk to care. Their houses, little more than crooked piles of wooden clapboards, hold absolutely nothing that could fetch more than a couple of rubles. It’s all been sold to buy spirit, a cheap, high-octane alcohol. Entire villages live like that, and the local kids get wasted more often than they go to school. It’s kids coming from these situations, who have been abandoned by their parents, or found by Social Services, who make up the bulk of those in the orphanage system.

The kids in priyuts range from 3 to 16. If they were abandoned in the maternity ward or any time before the age of three, they spend their early childhood in a dom rebyonka. That is one of the few justifications for splitting up siblings. The Solnyshko currently has one such case. Last April, when Vova was 4 and his sister just six months, their mother left them in the Tynda train station to sell herself. She then used the money from the trick to get drunk and forgot about her children. The militsia only noticed the kids after several hours. They where taken to the local hospital, where they stayed until a place could be found for them. It took eight months before Vova was placed in Solnyshko and his sister was sent to a dom rebyonka in another town. They won’t be reunited for two years.

Even that’s not guaranteed, since children who live in a dom rebyonka often develop some signs of retardation due to a lack of individual attention in their early childhood. This then leads to them getting assigned to special homes for debili, homes for the mentally retarded. The debili are the most notorious of Russia’s orphanages. Even the name for such institutions, psychoneurologicheskye internaty, has a sinister ring.

These dungeons, which according to Human Rights Watch sometimes imprison kids for conditions as curable as a clubfoot or innocuous as mild Down’s syndrome, continue the Soviet tradition of treating disabled people like lepers. If you’ve heard stories of children being forced to strip in front of peers, left in unheated rooms as punishment, or forced to stand naked in front of an open window in winter, chances are they were taken from one of these debili homes.

![feature2-1 tynda2]()

The kids at the Solnyshko are lucky in that the staff are sincerely devoted to helping them, which is by no means a given in Russian orphanages. But the range of problems is so staggering, and the staff has only a relatively brief period in which to gain their trust and help prepare them for a hostile future, that Tishenko says that no more than 30 percent will be able to escape the vicious circle of alcoholism and live relatively normal lives. A great sense of urgency hangs over their work at the Solnys

hko, because everybody knows that most of the children won’t find another sanctuary like it ever again. “Often, just when we start making progress with a child, he’ll be sent to a detdom,” said Kravchenko.

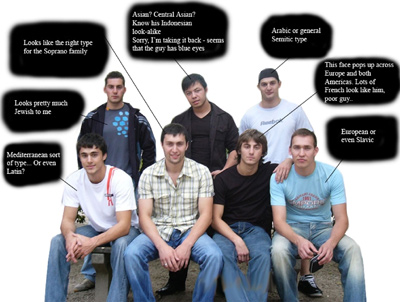

When a kid arrives at the Solnyshko, the first thing the staff does is ask if he’s hungry. According to Kravchenkothey, they almost invariably are, even when they are coming from another state institution. “It’s important to establish that we are concerned about their feelings immediately,” she said. “By letting them understand that we know they are hungry, we can establish some trust.” The kid is then washed, clothed and given a medical check-up. Generally, new arrivals are kept in quarantine for several days before they join the main group.

At first, most kids like the priyut. They are fed as much as they want five times a day, there are kids like them to hang out with, adults pay attention to them, and they don’t have to worry about basic questions of survival. Still, it is difficult for them to adjust to the strict regime. Used to the freedom that is associated with neglect, chores seem to them an unfair burden.

Gradually, most come to realize intuitively that having responsibilities implies that they are needed. The staff trusts the kids, even those who had formerly been pickpockets. It also undoubtedly helps that there really isn’t much to steal. Tishenko thinks that providing expectations for a kid who has never had anyone trust him with responsibility is at least as effective as one-on-one therapy in helping him adjust to life at the priyut.

One of the most difficult aspects of life for the children is dealing with their perceived rejection by their parents. “Even in cases where their parents beat them [about a third of all the orphans], the kids still love them,” Tishenko said. “Still more interesting is that the children want to save their parents, cure them of alcoholism.”

Tishenko encourages this sentiment, and never advises a kid to make a break with his parents. This strategy sometimes backfires, as with Yasya, the kid who saw his mother murder a woman. In another tragedy, a 14-year-old boy ran away from the priyut to be with his mother. He found her drunk and, when she told him to fuck off, he stabbed her to death. But Tishenko believes that the hope of someday supporting and reforming their parents gives most of the kids something to cling to.

At the same time, Tishenko tries to separate the kid’s sense of self-worth from his relationship with his parents. Even parents who are generally good about writing often slip into zapoi, or a Russian-style drinking binge, and completely forget about their children’s very existence. It is devastating for the kids.

Many kids treat members of the staff at the priyut like surrogate parents, calling them mama and papa. Kravchenko, Tishenko and others know all the kids and their problems individually, and really do love them. The staff even takes a perverse pride in the fact that many kids, when they run away from their detdoms, head straight for the Solnyshko.

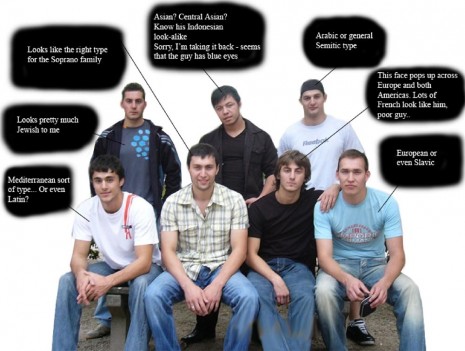

The scope of developmental problems at the Solnyshko is remarkable. The first thing I noticed is that most of the kids are very small for their age, a telltale sign of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. After spending a little time with them, it was clear that they are all textbook examples of what happens when a mother drinks heavily during pregnancy.

The younger kids were extremely uncoordinated and hyperactive. It’s hard to quantify, since all little kids are clumsy and like to make noise, but these kids were more chaotic than most. They were all sweet and really cute, but I don’t envy the nannies, who work in pairs, charged with watching over fifteen hyperactive kids aged 3 to 9.

FAS symptoms were particularly acute in two sisters, Dasha and Ira, aged 6 and 7. Both have bright, irresistible eyes that always seem to be looking up hopefully, maybe because they are so small that they look like 3-year-olds. They are mentally stunted as well. Ira is the only kid in the priyut with a physical deformity – she has an opening in the roof of her mouth called volchya past, or wolf’s mouth, that severely impedes her speech. She’s scheduled for corrective surgery in Blagaveshensk in February. She could have had the work done before, but her mother would drink away the monthly pension Ira received for her disability. Once the girls were already living in the priyut, Kravchenko established contact with their father, who came to pick them up. But after taking a look at them, he declined.

From what I noticed with the younger kids, they didn’t seem traumatized by being abandoned; it’s only with adolescence that the kids start manifesting psychological problems. The young ones are just kids, albeit ones who are behind the growth curve, both physically and mentally.

Ludmilla Aleksandrovna, the head nurse, said that pretty much every kid there shows some symptoms of FAS. They are constantly falling ill because of their weak immune systems, and many of the older kids have severe learning disabilities and difficulties in school. It is hard to isolate the cause of these problems, since many of these kids didn’t attend school regularly before moving to the priyut, and they have ample reason to have emotional issues that would also surface as learning disabilities. The growth defects could also be due to malnutrition. Still, no one doubts that FAS contributes to their troubles.

Some of the kids had never been to school before moving to the Solnyshko. One family of four kids from the Sershevo village, aged 13, 11, 9 and 8, studies in third, second, first and first grade, respectively. Most Russian 13-year-olds are in eighth grade, yet the oldest one from that family, Fedya, can barely read. He is one of the most outwardly troubled kids, constantly acting up in school and bullying other kids. The one boy with a black eye at the Solnyshko got it from Fedya.

During my visit, Fedya’s illiterate 9-year old brother, Vasya, asked me to read a letter from their mother. Before I got through the opening greetings, Fedya had grabbed the letter and threatened to smack him upside the head for showing it to me. Later, when Tishenko read it to Fedya, the boy wept. Tishenko said that it was clear from the tone that his parents were still drinking and not about to make any effort to retrieve their children.

In the past, kids found by chance in the taiga have arrived not knowing how to use a fork or what toilet paper is. Nobody knows how many families there are out in the taiga living in conditions of poverty that stuns even the hardened workers of the Solnyshko.

Compared to all of these problems, the fact that some 30 percent of the kids smoke seems trivial.

By any reasonable standard, the conditions at the priyut are atrocious. The building, intended as a kindergarten, wasn’t meant to be lived in and has made the transition awkwardly. The young group all sleep in one room, while the old group lives eight to a room; there is one shower each for the boys, the girls and the young group; the roof leaks in several places; it’s woefully understaffed, with a single psychologist who is only halfway through his studies, for 47 extremely disturbed children; drugs that could help the children cope with their depression, anxiety and ADD are, of course, unavailable; the food, while plentiful, is devoid of any flavor or nutritional content; it’s too cold to go outside much of the time, meaning the kids are confined to the overcrowded building; each kid only has three pairs of clothes, all little better than rags; they can’t afford toys; for holiday presentations, the kids make their costumes out of discarded candy wrappers. The list just doesn’t end.

But by local standards, the Solnyshko has entered a new stage of stability. For the two North Koreans living there, it must seem positively luxurious.

When the priyut first opened on the grounds of the kindergarten, there was virtually no money for a makeover. All the miniature furniture was only gradually phased out, replaced by donations and scavenged items. Back then, there was just enough money for salaries and food, and that only because of donations by foreign charities. While the kids’ clothes now are very low quality, at least they can all dress differently. In a photo Tishenko showed me from 1998, there were only about 7 varieties of one-size-fits-all t-shirts for a group of 40 kids.

Starting in 1999, the federal government took notice of the priyut. They now receive enough money to maintain a minimum level of care that only a few years ago seemed unimaginable. Its annual budget of 5 million rubles is provided by the oblast, and that covers the costs of food and clothing, as well as the staff’s salaries, which range from 2500 rubles to 4500 rubles. The federal government provides free health care and various pieces of equipment. Last year, for example, it supplied the priyut with two computers and a minibus. Each year, the government covers the cost of several weeks in a summer camp as well.

The federal government also opens a small bank account for every kid in the orphanage system (it can grow to up to 20,000 rubles, depending on how long they were in the system) to help them get on their feet when they turn 18. Theoretically, once parents lose custody of their child, they surrender the right to sell their apartment. However, since most alcoholics have long ago sold their homes in order to buy more booze, upon graduation the kids are put on a list to receive federal housing in the town in which they are registered.

Charity marginally helps fill the huge gap between what the priyut needs and what it can afford. But Chilchi is so isolated that international aid, mostly food and clothes, only trickles in via Blagaveshensk, while local companies couldn’t care less about the orphans. Average people from around the region donate what they can, although their means are understandably limited. Solnyshko employees regularly make the rounds at Tynda’s market asking for any handouts the stall owners can spare.

Visiting these kids is a truly sobering experience. Their condition is a far more direct and painful evidence of modern Russia’s complete degradation and moral bankruptcy than the looting of the country during market reforms, the lack of fundamental rights such as health care and heat, or even the war in Chechnya. Because, while these well-publicized crimes are abstract issues for the people who perpetrate them, the problem of orphans is an intensely personal and individual one. That these kids’ parents are alive and have inflicted such cruelty on their own children is mind-numbing. The consensus among the adults at the Solnyshko is that poverty is at the core of Russia’s problems, and that alcoholism springs from this poverty. Like America’s Indians: destroyed and drunk.

And while Western journalists and Moscow’s nouveaux riches cheer the daily opening of new boutiques and shopping malls within the MKAD, the situation for Russia’s abandoned children throughout Russia is decaying at a depressing, inhuman rate. True, Solnyshko now receives more money than it did a few years ago. But the flow of kids into the system continues unabated. As Tishenko said, the answer is not in building more priyuts or better financing. “The government needs to pay attention to its citizens,” he said. “The example of Germany amazes me – that there aren’t poor people, that the government actually helps people in need.” He notes with bitter irony that American and Israeli organizations provide more material help to the priyut than local Russian companies. Highly profitable companies that make a killing stripping gold and timber from the taiga don’t give back a kopek. The priyut collects more stuff from simple Russians – pensioners, saleswomen in the markets, and non-drinking families who earn a few hundred dollars a month – than from local industry.

It seems that no one, from local biznesmeni all the way to Moscow, gives a shit. From out here in the far-off regions, it’s disgustingly comical to watch politicians on TV talk about Russia integrating with Europe, when the real issue is how to stop the whole country from dying of cirrhosis. What European country would tolerate the Solnyshko, or the situation that allowed for it to be created? The sad fact is that the USSR was far closer to providing a European-level safety net; at least it offered some form of social security. And while people in the Soviet Union were no teetotalers, drunkenness has skyrocketed since 1991. The explosion in the number of abandoned children, the soaring murder rate and declining life expectancy can all be linked directly to the phenomenal rise in drinking. Not coincidentally, it was Russia’s highest-ranking drunk, Yeltsin, who ushered in an era of vodka-packed kiosks offering cheap vodka to help the masses dull the pain of shock therapy.

The kids of the Solnyshko are not the only victims of this terrible era. Some estimate that up to a million children in Russia are homeless, and nobody knows how many more live unreported in villages, not going to school and drinking every day with their parents. Tishenko admits that it is usually just luck when they stumble upon kids living in such conditions. These poor, stunted kids are the real face of modern Russia, the Russia outside of Moscow’s MKAD and IKEA hypermarkets. They are living symptoms of a national tragedy.

For donations[NOTE: THIS INFORMATION IS LIKELY OUTDATED SO CHECK FIRST]

676266 Amurskaya obl., Tyndinsky rayon P. Chilchi, ul. Lenina, 5, Sotialny detsky priyut Solnyshko. Tel: ask the operator to contact Chilchi, Amur. obl. and dial 2-23. Or contact jake@exile.ru to find out how to donate money

This article was first published in The eXile on January 22, 2003

Irregular warfare’s Agent Orange

Irregular warfare’s Agent Orange